About Bradford McDougall

Bradford McDougall is a Connecticut based sculptor who has been working with a variety of mediums for over thirty years. McDougall creates large-scale steelworks with an aim to manipulate existing environments and challenge how the placement of art can alter the experience of a given space. After numerous commissioned projects producing practical furniture for RT Facts, a Connecticut based furniture seller, McDougall has come to pursue a balance between his love for playful sculpture and his success in function driven furniture design.

McDougall has a BFA in furniture design from RIT. His work has been featured in publications such as The Wall Street Journal and The Baltimore Sun. McDougall’s artwork is part of Tools As Art: The Hechinger Collection, and the Mattatuck Museums personal collection. He can be seen live and in action on the Forged in Fire episode that went viral, Season 5 Episode 2.

Forged in Fire, Season 5 Episode 2

Bradford McDougall News Archives

Sculpture problems gone with dog

Commission decides it won’t try to curb this Woodbury art

By Nicole Neroulias

WOODBURY – A heated year-long debate about whether art within the historic district can be regulated has come to a quiet end. Members of the Historic District Commission decided last month to shift their attention to construction projects, light wattage and sign designs.

The commission, charged with maintaining the historic integrity of Main Street, received several complaints last fall about three items: a large golden nude at Tom Arras’ residence at 75 Main St. South; Frank Martinelli’s black and white sculpture outside Good Hill Mechanical Contractors at 53 Main St. South; and Stephen Segre’s 20-foot-tall orange sculpture outside the Forge and Anvil at 442 Main St. South.

In the spring, commission members decided only the latter fell under their jurisdiction over “affixed” structures and requested that Segre apply for a certificate of appropriateness. After Segre refused, zoning enforcer Jim Testa visited the site in June. He found that the sculpture rested on pads, refuting the commission’s belief that it was bolted to the ground.

“Because of its base, we decided that the sculpture was not affixed, the way a building or a sign would be,” said Marion Griswold, commission member. Research into the varying regulations of artistic displays in other towns yielded nothing but more confusion, she added, fur- ther encouraging the commission to drop the issue.

Soon afterward, the three Main Street sculptures were joined by a 7-foot-tall orange puppy perched on the front lawn at 77 Main St. North.

As a precautionary measure, property owner Duncan McDougall said he checked with the land use office about displaying the sculpture, which was designed by his son, Bradford McDougall, a 1989 Nonnewaug High School graduate.

He said he has heard only positive feedback from residents. “Some people have asked me what we feed it and where we get its dog tags,” he said, chuckling.

Bradford McDougall said he designed the cartoonish canine called Barking Dog a year ago. It’s based on his 4-year-old daughter’s drawings. At his father’s request, he said he drove the 600-pound sculpture from Maryland to Woodbury, hoping to widen his market as an artist as well as expand his hometown’s cultural palette.

“I’ve always wanted to put a sculpture on that property,” Bradford McDougall said. “A year ago there wasn’t any hoopla about it, and when all this craziness started I thought we should put one up there to show people that they should all put sculptures in their front yards.”

Commission members have not commented on the new sculpture. Segre said he has not seen it, but felt the commission members “came to their senses” by dropping artwork from their agenda.

McDougall’s designs can be viewed and purchased at www.mcmailbox.com. Barking Dog is listed at $5,000, though Duncan McDougall said he’d be sorry to see it go.

“I never had a problem with any of the other sculptures,” he said. “I think they’re neat, and Woodbury could use a little more laughter.”

The Waterbury Republican, August 21, 2003

Roland Park artist creates by the yard

Sculptor: Neighbors’ lawns showcase the metal incarnations of a child’s fanciful drawings

By Jamie Stiehm

A blue elephant is rearing its head in Roland Park.

It’s standing on the lawn of a country cottage home on Hawthorne Road – a 12-foot-high plate steel sculpture made by a local artist who’s using the staid, tree-covered Roland Park environs as the backdrop for his outdoor metal menagerie.

Bradford McDougall, himself a Roland Park homeowner, is forging a series of giant animal sculptures based on the drawings of his 4-year-old daughter, Olivia. There’s not only the blue elephant, but an enormous orange barking dog that for a while sat in the front yard of his Oakdale Road house. And coming soon is a pink bulldog with purple polka dots.

The one-time blacksmith hopes that passers-by will develop a taste for his unusual form of metallurgical creativity. But large twisted metal pieces of modern art are certainly not what you’d expect to see in Roland Park, and not everybody’s happy.

“The reaction is very mixed,” says David Blumberg, president of the community’s civic league. “Some look and say, ‘Why not?’ Some look and say, ‘Why?'”

McDougall, a 32-year-old work-at-home artist, is using Roland Park as a sculpture showcase. He has lent or sold his pieces to various neighbors, based on the notion that if people try it or spy it, they might buy it.

“The new marketing is going to get kids to bug their parents enough that they have to buy it,” McDougall says in a dry jest.

It all began when McDougall knocked on doors last year and, with a bit of moxie, persuaded several neighbors on Oakdale and Hawthorne roads to display one of his large modern sculptures on their front lawns.

The whimsical works in metal, stainless steel and aluminum are a stark contrast to the residential architecture of shingles, stone and slate for which Roland Park is known. But some say the modern metal motif also illuminates a side of the community’s character.

Recently, law professor Tim Sellers stood outside and gazed fondly at the metal blue elephant in the greenery from his front porch. Just home from a family trip to England, Sellers explains why he, his wife, Frances, and others were willing to accept McDougall’s proposal to put the azure pachyderm on his front lawn – for no charge, a glorified advertisement of sorts.

“This is the nerve center of Baltimore art,” Sellers declares. “We’re not Homeland. We’re not Guilford. We’re that funky Roland Park.”

“Everyone’s begging for one,” he says of the sculptures.

His daughter, Cora Sellers, a 16-year-old Bryn Mawr School student, says the massive jagged sculpture of what McDougall calls the “chicken-elephant” creature is the envy of her friends.

The nearby placement of other McDougall artworks close to the neighborhood’s sidewalks creates the sense of a connected series, Cora says. “It makes it fun to go for a walk.”

The sculptures are also conversation pieces among adults.

“I don’t necessarily get it,” Blumberg, the civic league president, confesses. “My taste is more traditional and I find the sculptures ponderous. But I’m a Baltimore City Republican, so why should I think different is bad? And I do like elephants. If there’s no message there, then I like it better than if there were a message and I missed it.”

When asked whether anything can be done to conceal the artwork from public view, Blumberg says the answer is no, the display violates no legal codes or covenants.

In the neighborhood, the chatter goes on. Frances Sellers, Tim’s wife, says the elephant is anything but a white elephant.

“We hear a lot of discussion about it, like whether it’s actually a seahorse,” Frances Sellers said. “People ask if it’s like (Alexander) Calder.”

McDougall says Calder, the famed late American sculptor, is indeed a key influence.

Another “inspiration point,” McDougall says, is his daughter, Olivia, whose drawings of imaginary animals he routinely translates into three-dimensional objects for the neighborhood work-in-progress.

“I thought, it’d be really cool to make these into sculptures,” McDougall says.

The sculptor is married to Therese Mulvey, 45, who works in market research. He splits his time between creating in his backyard workshop and taking care of daughters Olivia and Georgia Blue. He studied fine arts at Rochester Institute of Technology and has since made a career from wood cabinets and metal sculptures.

The life of an artist in Roland Park is anything but lonely, he says.

“This is more fun than doing the whole gallery scene,” McDougall said, “since it’s more about me.”

But it’s also hard to make cold hard cash for an early McDougall. One couple who lives across the street bought their outdoor sculpture for $4,000, McDougall said.

But the other works have gone unsold despite their prominent public display – some would say free advertising – in one of the city’s most affluent areas.

In short, Roland Park’s moral support for the sculptures has proved stronger than its financial support.

“That’s the downfall, that I don’t sell that much,” McDougall says.

The exception is a couple who were complete strangers before he came to their door. Clair Francomano, a geneticist, and John Thorpe, the head of St. Paul’s School, were the lone neighborhood buyers.

The couple didn’t buy one of McDougall’s fanciful animals. But they did take an instant liking to one of his abstract sculptures, “Y — Livia,” two brushed stainless steel discs supported by a staff on a large slate pedestal. Once the shimmering discs were installed by Francomano’s bamboo grove, she and her husband became believers and wrote McDougall a check.

“It just belonged there and seemed made for the space,” Francomano says. “We couldn’t imagine the front yard without it.”

The geneticist says she and her family think of the visual contrast between the century-old houses and the new art as a refreshing duet.

“The very modern sculptures are in harmony with the very traditional architecture,” Francomano says. “I don’t think John and I would have in a million years thought of buying a sculpture, but once it was there, it had to stay there.”

Meanwhile, back at the McDougall home on Oakdale Road, the family continues to churn out artwork.

“We’re a team, right?” McDougall says to Olivia.

“I painted it,” Olivia says, referring to her “barking dog” sketch.

McDougall shrugs and concludes, “This fame is going right to her head.”

The Baltimore Sun, July 17, 2003

Mailboxes Post Their Own Mark

Can’t Afford to Turn Your House Into a Statement? Start on the Unit Out Front

Charles Beaumont, and orthopedic surgeon in Woodbury, Conn., likes to show he’s a nonconformist. So he adopted a “Rastafarian” look–for his mailbox.

Charles Beaumont, and orthopedic surgeon in Woodbury, Conn., likes to show he’s a nonconformist. So he adopted a “Rastafarian” look–for his mailbox.

The blue metal box, for which he paid $225, has dozens of “dreadlocks” made of spark-plug wire hanging down in 2 1/2-foot-long strands. “This is a way of announcing a little bit of individuality,” says Dr. Beaumont, whose 20-acre property also features a mailbox decorated with silver frogs and another adorned with green crickets wearing purple hats. (The mailbox he actually uses for receiving letters is mounted on a swivel and painted fire-engine red.)

Not everybody has the time or the money to become their own architect or renovate their entire home into a personal design statement. So homeowners are going postal, literally.

Mail Bonding

Barbara Yeargin, an insurance broker who lives in a Cape Cod-style house in Laguna Beach, Calif., recently ditched an old tin mailbox for a gray-and white, cast-iron model that cost about $1,000. “I wanted something more stylish, that would go with the style of my house and make it special,” she says. “I think a mailbox says a lot about the people who live there; what they have out on the street that collects all their important mail.”

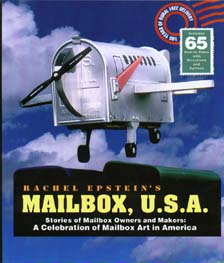

This attitude has created a cottage industry for custom-mailbox builders. Baltimore artist Bradford McDougall, who designed the “Rastafarian” mailbox, says the Neiman Marcus store in Washington, D.C., will begin carrying some of his mailboxes next week. Wayne Burwell, president of Mailbox Factory Inc. Of Kirtland, Ohio, says business has been growing by about 30% annually since he started it in his garage 12 years ago. Prices range from $85 for a race-car shaped mailbox to $600 for an exact replica of a customer’s house. Other Mailbox Factory products under construction include a 4-foot-tall, dollar bill-shaped mailbox Mr Burwell is designing for a mortgage broker, and another one that looks like Winnie-the-Pooh.

Some homeowners say a unique mailbox can lead to a certain cachet in the community. Michael Shepard, a cigar-smoking financial planner in Moreland Hills, Ohio, recently paid $1,200 for a mailbox that looks like a hand holding a big stogie. “The mayor and everybody else drives by and checks it out,” he says. “The mayor says there’s nothing like living on the edge.”

But even here, size matters. Streetscape Inc., of Huntington Beach, Calif.–which sells mailboxes for as much as $1,100–says big mailboxes are hot. For instance, Verna Harrah, of the Las Vegas casino family, recently bought a solid brass mailbox for her Beverly Hills, Calif., home that was a foot tall, a foot wide, and 2-feet long. Price: $600.

While there is a minimum size for mailboxes (they can’t be any smaller than 5 inches by 6 inches by 18 inches) there is no limit to how big they can be, says Mark Saunders, a U.S. Postal Service spokesman. And there aren’t any rules about how strange they can be. “Local postmasters will look at bizarre mailboxes on a case-by-case basis to make sure they’re not a safety hazard,” he says. What kind of boxes do mail carriers see on the rise? Vandal-proof boxes.

Not Attractive, but Strong

Mr. Mailbox of Norwalk, Conn., touts a “virtually indestructible” box for $279. Made of quarter-inch steel plate, it weighs 60 pounds, has an optional padlock and can be welded onto a $99 concrete-filled post. “It’s not the most attractive, but it’s by far the strongest,” says Mark Johnson, company president.

Sometimes, people need to resort to drastic measures. During the past dozen years, vandals destroyed three mailboxes in front of the Annapolis, Md., home of Kathy Mudd. “At one time I had a kitty-cat mailbox,” she says, “and of course they tore it to pieces.” So this time, she decided to get tough: She paid $1,300 for a steel “Nailbox,” with about 100 long nails welded all over it, and a baseball bat imbedded on the outside to look as if it had already been vandalized.

Mr. McDougall of Baltimore, who designed the box, says he was inspired by a scene in the movie “Stand By Me,” in which youngsters destroy a mailbox. “This was the mailbox that fought back,” he says. “It was like a big porcupine, covered with nails.”

Ms. Mudd says the Nailbox has met with mixed reviews. “Some people say, ‘That’s a really cool box,’ but most people think I’m strange.” Still, it has its advantages. “It makes it easier for people to find my house.”

The Wall Street Journal, May 15, 1998

Letter Perfect

When was the last time your mailbox made you smile? If your letter repository is one of Brad McDougall’s original creations, you’ll get a whimsical jolt every time you see it.

McDougall, a Baltimore furniture designer and blacksmith, has been selling the one-of-a-kind mailboxes since 1991,when his first effort won an award at a craft fair in New York state. The mailbox pictured is called “Goldie,” a tribute to the “Laugh-In” days of actress Goldie Hawn. McDougall’s work is available locally at craft fairs and at Neiman Marcus,5300 Wisconsin Ave., in Washington. Or you can orderfrom him directly at 410-467-1381, or check out his Website at www.mcmailbox.com. Prices range from $440 to

$3,000.

The Sun, May 31, 1998

Boxes Rebellion

Brad McDougall is making a name for himself with a line of witty boxes that are as tough as nails.

Somebody had to help the mailboxes fight back. After the movie “Stand By Me” hit theaters in 1986, the juvenile prank of smashing the defenseless boxes with a baseball bat grew to epidemic proportions in artist Brad McDougall’s hometown of Woodbury, Conn. So, for his entry in a mailbox design contest at Rochester Institute of Technology, McDougall fashioned a steel box with sides a half-inch thick and 220 giant nails spearing through the top. With time, rust would add an extra threat of tetanus. It was ingenious warfare, an invention that would have made any fifth century barbarian proud. And just so would-be box-bashers couldn’t miss the point, McDougall smashed his own Louisville slugger on top. “No one wanted to buy it. Everyone was afraid of it,” he says. Good. That was the idea.

McDougall has since expanded the designs with both blatantly threatening motifs – including a thin black snake, jaws open at the door – and more harmless critters such as crickets, caterpillars, crows and lizards. Like other famous crime-fighters (e.g., Spiderman, Superman, Batman, …), McDougall has a day job. “I’m a carpenter,” he jokes, taking his voice down a notch befitting the manliness of the title. In truth, he’s a woodworker. The 26-year-old and his wife Thérèse, a demographics researcher, moved to Baltimore last year when McDougall signed on to help metalworker John Gutierrez construct the Art Links miniature golf course for Maryland Art Place.

Now his days are spent designing and building chic, modernistic furniture and accessories: chairs, stools, tables, chests, beds, fireplace andirons. His pieces can be found in galleries and craft shows from Philadelphia to Denver. “They’re very traditional designs,” says McDougall, “but they tend to be very light in feeling. And always pretty much curvaceous in some way.”

Still, it’s those whimsical, handcrafted mailboxes that remain the star of his show, gaining exposure at such places as the American Visionary Art Museum gift shop and the prestigious American Craft Council Craft Fair. McDougall’s current favorite is the Dread-Lock Box, with its flowing “braids” of electrical wire- 750 feet of it- pulled through holes in the box.

Spending $500 to $2,400 on a mailbox designed to attract attention, and potential thieves, may sound like a risky proposition, but McDougall insists that once planted, his artwork is there to stay. The boxes themselves weigh up to 110 pounds each, and McDougall mounts them on the client’s choice of railroad rails or wooden posts driven three feet into the ground. “I made one for my mom,” says McDougall, “and a girl’s car slid on ice and hit it. The box was destroyed, but it held her Subaru up in the air. They needed a towtruck to lift it off.” -Vikki Valentine

(For details on McDougall’s work, call 410-467-1381)

Style Magazine, July/August 1997

Letter Perfect

It’s deliciously appropriate that Carole Peck met her future husband, Bernard Jarrier-Cabernet, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art more than 25 years ago. It was a major exhibit of fine American furniture, as they recall, including (of course) some magnificent dining room pieces.

Today, Peck’s innovative, health-conscious food is showcased in a playful, multi-hued setting at the Good News Café in Woodbury, Conn., which her painter-husband oversees with loving attention–right down to blending the correct yellow paint for the walls of one dining room and personally reupholstering the booth seats when necessary.

Peck, a chef who recently published The Buffet Book (Viking Press), creates whimsical and imaginative culinary art that rivals the sculpture, paintings and decorative objects with which she and her husband have filled the café.

No decision is mundane. Having originally intended to be a potter and sculptor, Peck is as enthusiastic about snagging the right plates for her Mediterranean seafood salad or wok-seared shrimp as she is about hunting down the perfect imported olives. She may have 12 to 15 different tableware patterns in simultaneous use, and this self-described “plate fanatic” is always on the lookout for more.

In each corner and at every vertical level of the café, there are unexpected visual attractions. The decor evolves with the whims of Jarrier-Cabernet, and has included a huge sculptured cobra looming over diners; delicate metal people tip-toeing across a tightrope, holding tiny white lightbulbs to illuminate the bar; and a most unusual metal goat.

Bold paintings hang nearly canvas-to-canvas in the dining room. Last year the café presented a major retrospective of the work of Natalie Van Vleck, considered the first significant American woman cubist painter. To celebrate the publication of Peck’s cookbook last summer, the couple mounted an ambitious exhibit of work by painter Albert Luden and sculptor Georgia Blizzard. This summer brings abstract paintings and large three dimensional collages by the late stage designer Edward Gilbert. The outdoor sculpture garden may feature huge horses and snakes by Karen Petersen or the funky mailboxes of Bradford McDougall.

Are regulars like author William Styron and New York Pops founder Skitch Henderson attracted by the pleasures of the palate or the palette? Who can tell? “The point is, we want to offer excitement, on the plate and on the wall,” Peck says. It’s a goal that they have realized beautifully. The Good News Café is at 694 Main St. South, Woodbury, Conn.; call 203-266-4663.

American Style Magazine, Summer 1998

Nailbox

The mailbox, with the baseball bat and spikes, was made when I was a student at Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT). I was studying woodworking and furniture design. A local gallery sponsored a student show of customized mailboxes. The movie I’d recently seen was Stand By Me. The opening scene showed teenagers, running around in a car, smashing mailboxes with a baseball bat, a Louisville Slugger. So, I made a deterrent mailbox, one that couldn’t be smashed.

“Nailbox” has about 220 spikes on it. They are 6″ galvanized spikes, all spot welded from the inside to seal and waterproof it. The bat is a Louisville Slugger, which was smashed on the top to produce a splintering effect. To get the bat on, I had to drill holes almost all the way through it and smash it on with a 15-lb. Sledge hammer and block of wood. The mailbox is 3/16″ plate steel, all welded together. It is completely indestructible. Most people laugh when they see “Nailbox.” They say, “Wow, I could really use that.” But, they’re scared of it at the same time. They definitely know what the baseball bat is there for, ‘cause in this area everybody’s mailbox has been smashed once or twice.

I knew a couple of kids during high school who smashed people’s mailboxes. They weren’t caught, but they were chased. They were just out having a good time. Something to do in a boring small town. Like some other towns around here. Definitely. Nowhere to go. They just find something to do in their cars, like smash mailboxes and drive around fast.